The Golden Gates

Shallow Depths with Rich Rewards

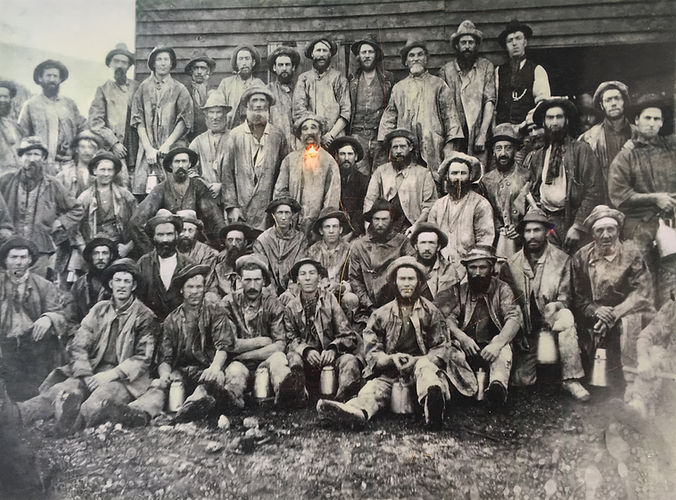

The discovery of gold buried under Broomfield Gully in 1872 set off a chain reaction of intense prospecting and mining operations along the northern side of Spring Hill where three new leads were revealed. These mines found their riches by working down the shallow but highly profitable tributaries of what was to eventually become the richest deep alluvial goldfield in the world.

The power of persuasion

The discovery of a completely new gold system started in Broomfield Gully where James and Sarah Brawn had their home with their son Edward. James was a local auctioneer and Sarah, in her spare time, made a study of gold, where it might be and where it wasn’t.

Edward, with his mining partner Leonard Carter, had a liking for other prospects, but Sarah firmly convinced the two to sink a shaft in the Gully which continued deeper than expected. They then sought further mining experience and partnered with William Graham.

Disappointingly, the shaft bottomed without results, however Sarah persuaded them to drive over the deep ground and sink a ‘winze’ in the bottom of the drive. They did and they struck wash, but as it was getting dark they took a bucket of it home to soak overnight.

In the morning of 11th May, 1872, they panned the bucket to reveal 383g of gold. They called their new mine ‘The Golden Gate’.

Left: Plan of Block Claim, Broomfield Gully 7th May 1872.

Note that it was registered as an alluvial claim adjacent to Nelson's quartz claim and the first gold was discovered only 4 days after the claims registration date.

‘The Golden Gate’ created a great rush of prospecting on this hidden goldfield and soon new discoveries began to revitalise mining in Creswick which had been waning since 1864.

The new beginning

Syndicates of local investors and farmers were quickly formed and secured the right to mine on the freehold lands that spread north from the foot of Spring Hill, with local land owners negotiating an entrance fee and royalties of 7½ to 10% of gold produced.

Throughout the mid 1870s mining operations intensified along the newly discovered Lewers, Lewers Western, Reserve and Spring Hill Leads and by the late 1870s, no fewer than 20 mines had produced nearly five tonnes of gold and a highly profitable return on investment.

They had discovered the richest deep alluvial gold leads in the world and investors and entrepreneurs now scrambled to secure their own rights to the wealth that lay ahead.

Above: Allan’s New Plan of Creswick, Kingston and Smeaton Mines, 1876. Note the mining titles already secured stretching well to the north of Spring Hill.

Below: Spring Hill. Inset taken from 'Creswick Gold Field' Mining Department Melbourne, 1880.

Mr Alex Lewers - a shrewd investor

“It is narrated that a land owner at Spring Hill had become indebted in some, not large, amount to one of the banks and the authorities in Melbourne, by and by becoming dissatisfied with the security, insisted upon their local manager, Mr Alex Lewers to take up the mortgage himself under penalty of dismissal. The manager did so very reluctantly. He, however, formed a small company who set to work to mine the paddock and did so with a brilliant success.” The Argus, 1876

Lewers not only helped form the Lewers Freehold Company, he also received 10%

of all gold produced by mines on his land

– a business model that assured his prosperity.

Above: "Lewers Freehold Mining Company" by W. Tibbits, 1874.

The typical surface works of the early mines are illustrated here: an engine house, poppet head with winding gear and a tram line for dumping the mullock and tailings. Lewers Freehold had a horse drawn puddling machine at ground level, however as the mines advanced, puddling machines were raised to the level of the Landing Brace and their operation was driven by steam power.

LEWERS FREEHOLD MINING COMPANY

APRIL 1873 TO FEBRUARY 1875

GOLD PRODUCED

395kg

CALLED UP CAPITAL

£630

SHAREHOLDERS

20

DIVIDENDS/ROYALTY

£58,520

Above: 'A view of Baron Rothchild Gold Mining Company's Claim, Spring Hill... Creswick, June 1876".

Note the depiction of Kangaroo Hills, Forest Hill and Spring Hill in the background. The mine also has two elevated puddling machines. Photo: Creswick Museum

Above: "A view of Dykes Freehold Gold Mining Company's Claim, Creswick... Spring Hill, April 1878".

Dykes Freehold was one of the first public companies floated on the new goldfield. Between 1877 and 1881 the mine yielded dividends and royalties of over £69,000 for an investment of only £5,850. Photo: Creswick Museum

Above: Spring Hill Early Mines – paid capital, dividends and royalty, gold produced and depth of shaft ~1879

Finding the leads

With local mine names like ‘Hit or Miss’ and ‘First Chance’, positioning a mine had always been a game of speculation. This challenge however was greatly assisted with the invention of the Diamond Drill and its ability to bore through the earth to reveal core samples of the geology below.

This information now allowed mining companies to identify where to place the mine in relation to the lead and where best to sink the shaft to avoid the presence of drift and water.

Above: A Diamond Drill at work

Top: Map showing bores over the goldfield. The State Government contracted the majority of diamond drilling.

Above: As the diamond drill cuts through the earth, samples of the geology encountered are cataloged and used to build an understanding of where the leads were and the depth of the gutter.

A man with a vision

In 1875, Martin Loughlin, a Ballarat miner and investor, alongside William Bailey, EC Moore, JA Chalk, R Orr, D Ham, E Morley and H Gore, bought up all the private land over the projected trend of the deep leads and together they created the 6,000 acre ‘Seven Hills Estate’.

By carefully subdividing the estate’s freehold to mining rights and periodically floating public companies (which he and associates also controlled), Loughlin had great influence on how the goldfield was developed and within twenty years he had become one of Australia’s richest men.

Martin Loughlin.

Drawing by John Druce